Lean in Japan

I have spent a week touring the Nagoya area to visit companies applying the Toyota Production System. They varied in size and industry, but had the following common traits:

- they are not doing this for fun or because some consultant told them so, but to survive

- they are passionate about their products, from steel coils to second hand books

In this post, I will share what I saw over there on the shop floor, and what a software engineering team might learn from it. Here’s the gist of it:

Most of the work being performed by a software engineering team is hidden, use visual management to make it visible

The role of the team leader is to support operators in their day-to-day job, which means he should be both knowledgeable and available

Not knowing how to perform a task is not an interesting challenge to solve for the operator, it is an issue for the management team

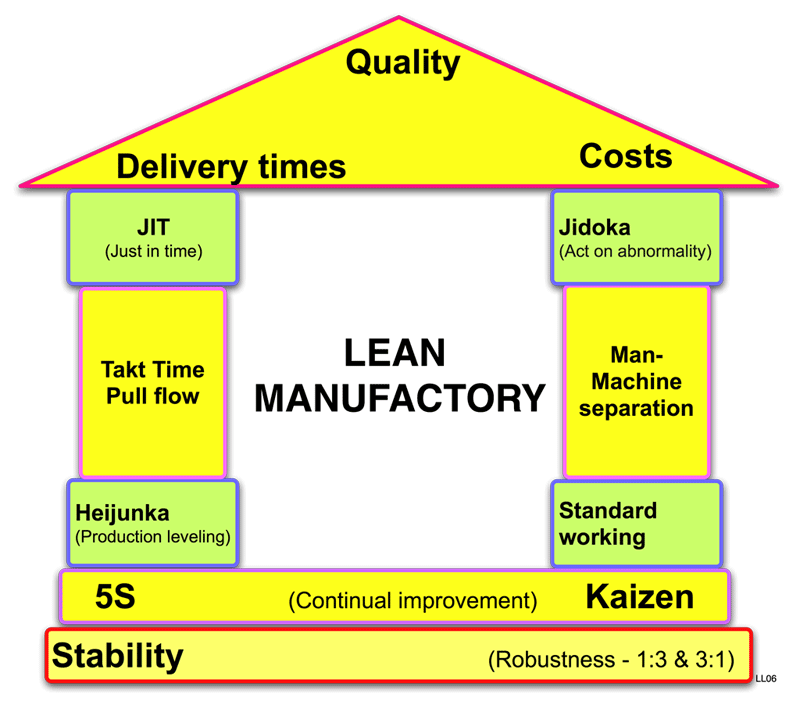

The dreaded wikipedia image

Visualize what has to be done, and what is going on

When you visit the shop floor, even though you don’t know anything about the steel coils industry, you can see what is going on. You can see the stock of raw material, you can see it being transformed by a series of machines, and you can see the stock of finished goods waiting to be shipped to the customers.

The shop floor in a steel coil factory

When you visit the office of a software company, it is hard to see all of this. Often all you can see is a bunch of people banging on their keyboards. It means that it’s hard to answer the following questions:

- is customer demand satisfied?

- is the team experiencing issues during production?

Visualize customer demand and current production using Kanban

Kanban can be used to visualize what has to be done, what has been done, and what is being done right now. Kanban cards represent orders from the client, that have to be fulfilled. In the case of software development, the client often is proxied by the Product Manager / Product Owner.

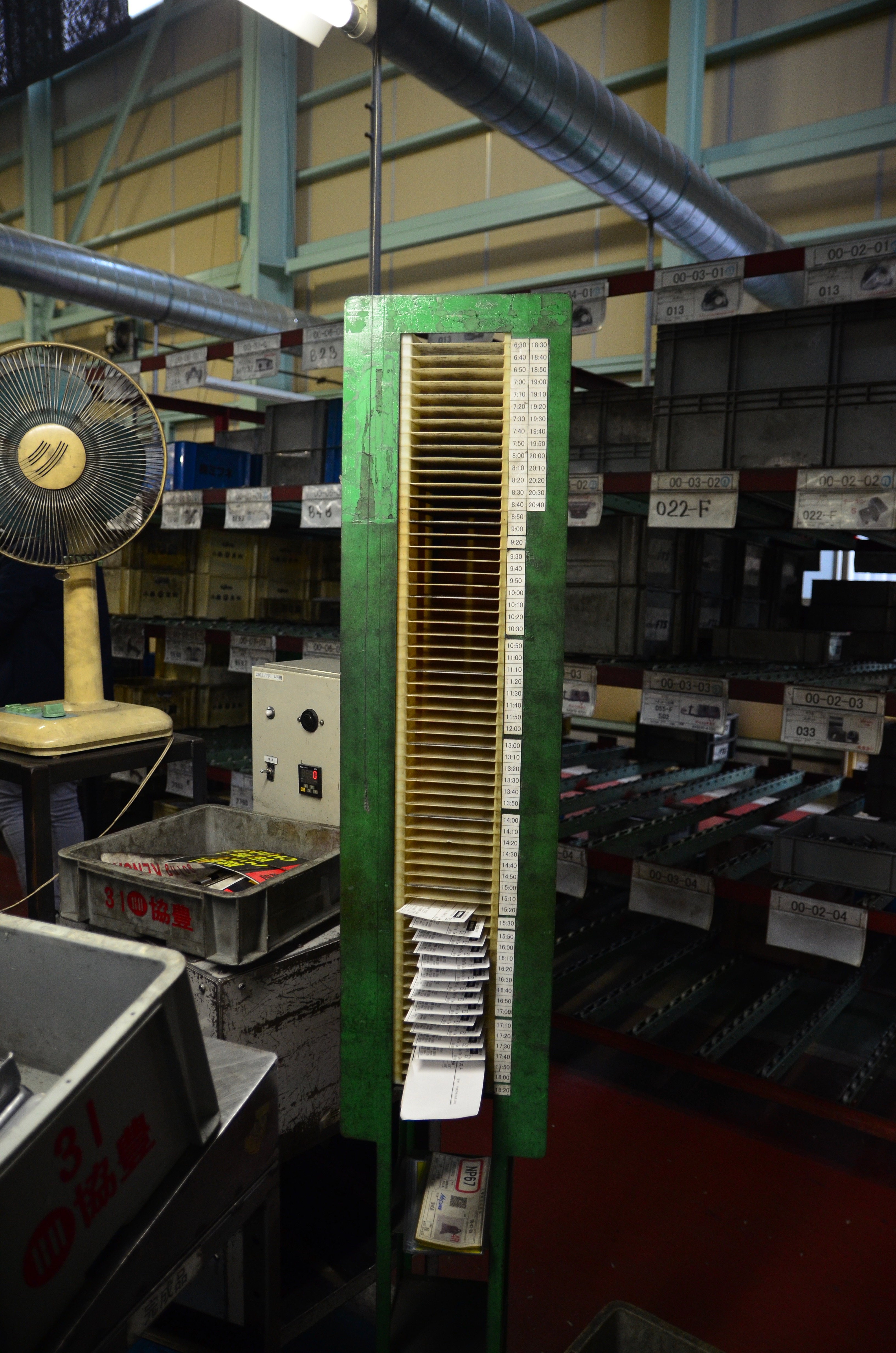

Kanban cards representing customer demand

Using Kanban cards, or any other visual artifact actually, to represent customer demand helps ensuring that the team is currently working on something that the client is waiting for. You cannot work if you don’t have a card showing that someone ordered your work. If the team’s production cannot satisfy customer demand, cards waiting to be done will start to pile up, and a reflexion should start to understand why. A good question to ask is:

Are there too many defects in what is being produced?

Produce according to a takt time

Detecting production issues is much easier is you’re working on a steady rythm. The takt time is the time interval at which work should be done. For instance, you can decide to have a takt time of a half day, so that every half day you ship one feature to the client. Of course, these numbers should match the global customer demand.

A takt time of 10 minutes

Every half day, you can either fail or succeed to deliver, and every failure is an opportunity to learn. Why couldn’t we produce this feature ? What went in our way ?

Are there too many defects in what is given as input? How can we reduce the fixed cost of shipping a product to the customer?

Spend your time adding value

When working, your time is split on two types of activities:

- value-adding activities

- non value-adding activities, also known as waste

Of course, some amount of waste is necessary. Writing tests is a form of waste: you spend time writing tests because otherwise you would spend even more time debugging your code. Nonetheless, you want to spend your time adding value as much as possible, and reduce waste to a minimum. In every japanese lean factory I went, quality was an obsession. They often spent a lot of effort doing final inspections to ensure they delivered only quality products to their customers. This is another form of waste. But they also used Jidôka, to enforce quality at every step of the production line. If an operator encounters an anomaly, or doesn’t know how to perform his task in the required time frame, he uses the andon system to notify his team leader and eventually stop the production line.

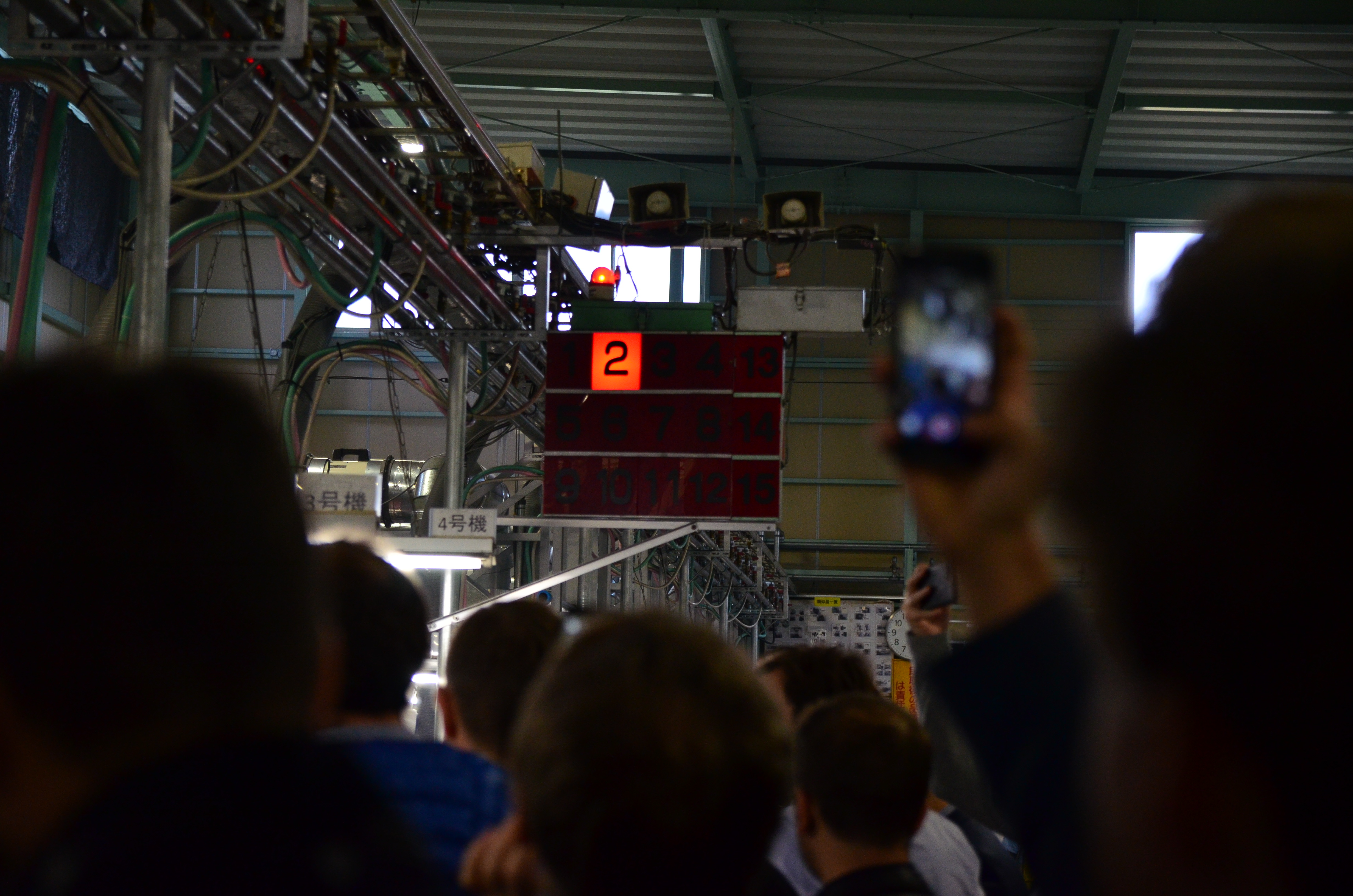

Operator 2 is in trouble!

As a developer, when the spec isn’t clear, the tests are brittle, your computer is too slow, or the API is undocumented, what do you do? You go on anyway, trying your best? You shouldn’t. You should stop working and call your team leader.

Standardize, then continuously improve

An operator on the shop floor knows in advance the exact sequence of movements he is going to perform in order to produce his next piece. And he knows exactly how much time each step is going to take.

The operator workstation, where standards are visible

It’s hard to imagine transposing this concept to the software development world at first. But if you zoom engouh on the tasks you perform as a developer, you start seeing patterns. Tasks that you repeat over and over again. Tasks that you can standardize, so that you have a baseline to improve upon. Standards are guidelines pushed to the next level, because they introduce the notion of standard time. How much time to create an empty React component ? How much time to add a GET endpoint to your Django REST API ? Standards are a powerful tool for operators to see if they know what they are doing, or if there are only figuring things out along the way. They are also great formation tools: they document the way of the team. Once you have standards in place, you can start improving, continously, Kaizen-style. Every issue is an opportunity either to create a new standard, or to improve the existing one.

I don't understand anything, but obviously after a kaizen things are better than before